2Blades’ “Mad Scientist” on the Move: John Lutterman Begins Next Chapter

John Lutterman joined the 2Blades Group at UMN - St. Paul in 2024, shortly after graduating from the University of Minnesota. Known affectionately as 2Blades’ “Mad Scientist,” John brought bold ideas and relentless curiosity to the lab. His last day is July 2, before heading west to pursue a Ph.D. in Plant and Microbial Biology at the University of California, Berkeley.

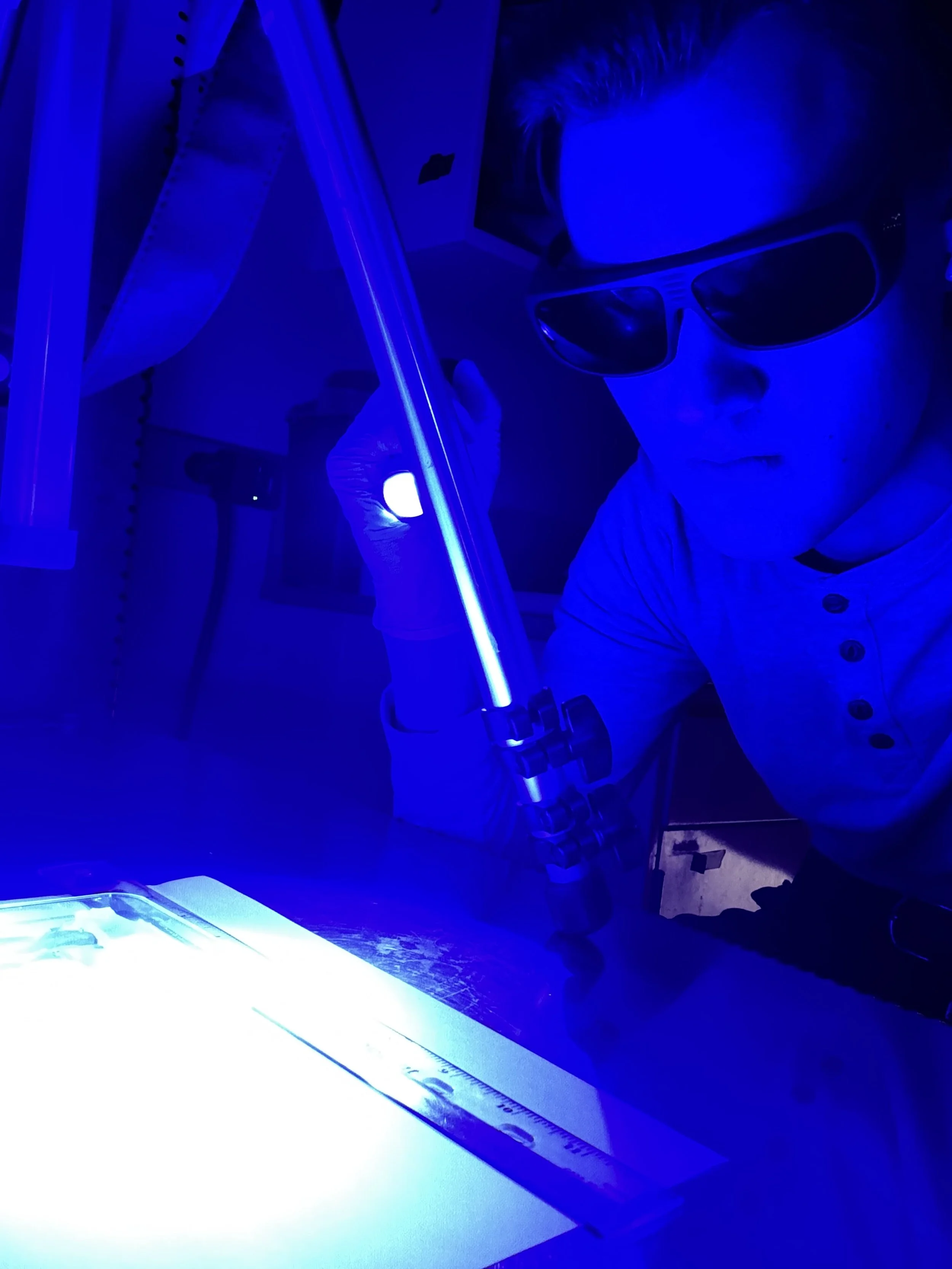

John testing out new equipment in 2Blades’ lab at the University of Minnesota - St. Paul.

When did you know you wanted to go into plant science?

When I started as an undergrad at the University of Minnesota, I was largely interested in molecular biology and gene editing with CRISPR. My initial pursuits focused on the potential medical applications of these technologies, but due to the COVID-19 pandemic, building connections and finding labs in this area had been severely hampered. At the end of my freshman year, I volunteered within mouse eye-disorder research, assisting the lab by taking DNA samples from various mouse lines and cataloging individual mice. This wasn’t entirely for me, but it got my foot in the door at a time when research opportunities were limited.

During my sophomore year, a friend pointed me toward a brand-new class on “Genome Editing and Engineering”, taught by a professor that I would later go on to work for — Feng Zhang. Joining his lab marked my introduction to plant biology. Work started off slow, but as time went on, I found that working with plants provided opportunities that few other organisms could offer: unique metabolisms with photosynthesis, simple whole-body studies, and unlike mice, they never tried to bite me! I truly enjoyed the “mad science” aspect of plant research, as I could do a lot of different things with them without worrying about harming anyone.

Still, in the summer of my junior year, I also volunteered within a human T-Cell engineering lab to broaden my perspective outside of plant biology. This was on top of my time within the Zhang lab, but ultimately, I found my time with plants to be the most meaningful. I saw the value in future-proofing our food, engineering crops to withstand harsh conditions, and protecting our farms from biotic and abiotic threats. So, following my graduation, I met with Josiah to learn all about 2Blades. It was an opportunity to keep working on plants and gain additional research experience before grad school.

At Berkeley, I will move out of crop disease and more towards metabolic engineering, looking at how we can engineer plants for novel purposes as future biofactories.

How did you end up at 2Blades? What was your first impression?

I actually met 2Blades’ plants before I met the 2Blades team! While working in a growth chamber for the Zhang lab, I started noticing random flats labeled “2Blades” showing up on the shelves. Not long after, I saw some UMN students spinning down Fusarium samples using our lab centrifuge. My immediate thought was, “who are these guys?” As I assumed they were visiting researchers without their own centrifuge.

After graduation, I had my first chance to meet 2Blades’ group leader, Josiah Mutuku; one thing led to another, and I was offered a position to join the 2Blades lab in St. Paul. It was a huge relief to find a research position right out of college, and I was excited by the chance to explore a wide range of projects. 2Blades let me follow my curiosity, try new approaches, and really learn by doing.

“It was a huge relief to find a research position right out of college... 2Blades let me follow my curiosity, try new approaches, and really learn by doing. ”

John performing AmCyan assays

Can you describe a particular moment that stood out to you during your time at 2Blades?

The moment that stands out the most was the first time I made a plant glow.

Monocot transformation is notoriously difficult, and my attempts up to that point were marked with at least a hundred dead or damaged maize plants, and even more drowned Setaria. Understandably, it took a while to get a quick and functional protocol up and running.

Initially, we pursued plant tissue culture: a process that requires weeks of careful culturing under sterile conditions, and if anything gets contaminated, you’re back to square one. It’s painstaking work, and we needed a faster protocol to test our genes. The major alternative was Agrobacteria transformation. Well described in dicots like Nicotiana benthamiana, the bacteria can supply genes in a transient manner, but few methods existed for its use in maize.

Throwing experiments at the wall, I submerged plants into a concentrated agrobacteria solution to try and infect them. Not surprisingly, this killed everything, and no plants could be recovered. Then, we tried surgically removing the cotyledon leaf to directly inject agro into the coleoptile. We hoped the bacteria would infect the meristematic tissue, thus regenerating transgenic leaves. Unfortunately, this process left many plants deformed and without any fluorescence.

Following these unsuccessful attempts, we tried forcefully pushing the bacteria through leaf tissue — similar to dicot infiltrations. After five days, we checked on our plants and finally saw a streak of glowing cells, as a fluorescent reporter marked which cells had our gene of interest.

That was my greatest relief. We finally succeeded in transient monocot expression.

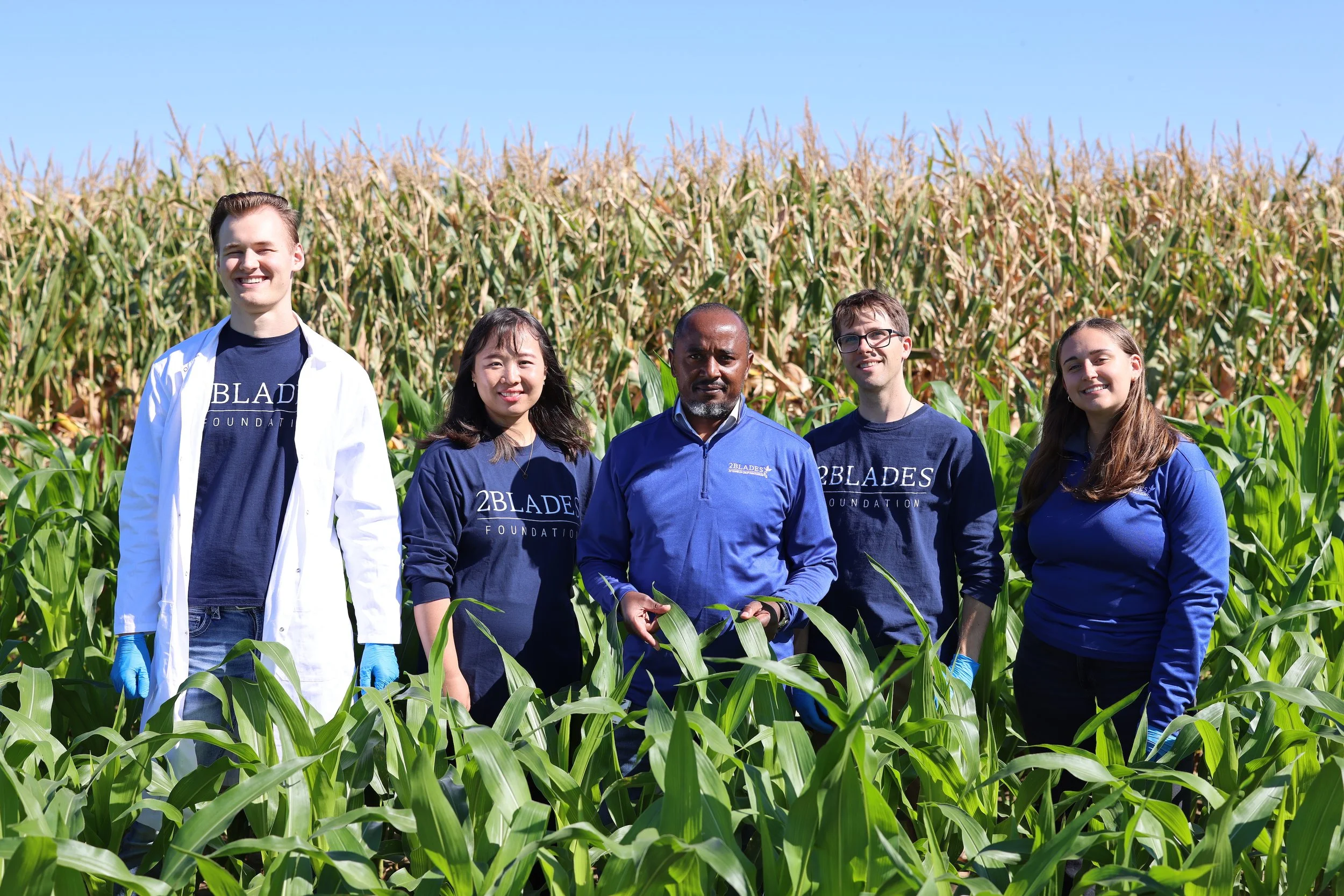

The 2Blades Group in St. Paul. From L to R: John Lutterman, Dr. Mengying Wang, Dr. Josiah Mutuku, Dr. Brian Rutter and Madelyn Jacobs.

What will you miss most about your time at 2Blades?

Out of everything, I will miss the people. Everyone in the St. Paul lab is incredibly kind and amazing to work around.

It has been amazing to do science with Brian, Tiana, Mengying, and the team. To throw questions on the wall and see what sticks; planning experiments based on nothing more than “I wonder what will happen if we try this….” 2Blades has fostered a culture where we aren’t afraid to mess up. Failure isn’t feared but seen as a valuable part of learning and progress.

Brian Rutter, in particular, has been an amazing mentor throughout my time at 2Blades, especially when it comes to experimental design and helping me imagine the next steps for any project.

“Our team is deeply grateful to John for joining us in our efforts to advance resistance to toxigenic fungi in corn and wheat. His infectious enthusiasm and creativity greatly enriched our work, and we’re confident he’ll carry that same energy into his PhD program. We’re committed to continuing the experiments he initiated and look forward to keeping him updated on our progress.”

Is there a moment or lesson from your time at 2Blades that you will take with you to Cal?

2Blades has taught me the ability to work as an independent researcher.

As an undergraduate, I was working on projects that already existed. I didn’t have any “ownership” over the direction of a project, which is wholly expected. As a student, classes came first over lab, so with graduation and employment at 2Blades, I was able to move projects forward in my own way. I had more time to build and plan experiments; I could work independently and see the bigger picture.

Because of 2Blades, I was able to reference not just what I did, but how I did it, and that brings a lot of extra confidence. Confidence that undoubtedly strengthened my graduate school interviews, as I could discuss what I specifically did, rather than relying on what our lab did collectively. I’m especially grateful to Josiah Mutuku and Feng Zhang for giving me this experience that I was able to highlight during my time in their labs. I doubt I could have gotten into the #1 public research school in the US without their support.

John already making new friends in the Bay Area!

What do you hope to be doing 10 years from now?

I am always drawn to mad science opportunities that cannot be imagined now!

There are so many challenges to solve in plant science, from engineering crops to withstand climate change to introducing entirely new metabolic pathways that nature never evolved on its own. Ever since high school, I’ve been fascinated by bioengineering and its potential to radically reshape what is possible in biology.

Unfortunately, a major challenge for gene editing is not around biology, but regulation and public perception. Plant gene editing comes with intense scrutiny around the “GMO” label, which is why I’m particularly interested in future research surrounding viral genome editing. It could provide scientists with a transgene free solution for DNA edits, as a virus carrying nucleases rather than a CRISPR gene avoids having a transgene entirely.

I could see this being an exciting new route for plant biotechnology. But regardless of the next big thing, I hope for my future endeavors to be as interesting as possible!